Samuel Pepys was a fascinating character. He wrote his famous diary between 1660 and 1669. He lived through the Commonwealth and saw the return of Charles II, the Plague and the Great Fire of London.

As the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, his responsibility was the Navy, and thus the Forest of Dean, which supplied the timber to build the ships.

He was born in 1633 and died in 1703. His life covered the reigns of Charles I, the Commonwealth, Charles II, James II, William & Mary and Anne.

1662 – 25th February

Great talk of the effects of this late great wind; and I heard one say that he had five great trees standing together blown down; and, beginning to lop them, one of them, as soon as the lops were cut off, did by the weight of the root, rise again and fasten.

We have letters from the Forest of Dean, that about 1000 oaks and as many beeches are blown down in one walk there.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1662 – 20th June 25th

Up by four or five o’clock, and to the office, and there drew up the agreement between the King and Sir John Winter about the Forest of Dean; and having done it, he came himself (I did not know him to be the Queen’s (Queen Henrietta Maria) secretary before, but observed him to be a man of fine parts); and we read it, and both like it well.

That done, I turned to the Forest of Dean, in Speed’s Maps, and there he showed me how it lies;

and the Lea-Bayly, with the great charge of carrying it to Lydney, and many other things worth my knowing;

and I do perceive that I am very short in my business by not knowing many times the geographical part of my business.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1662 – 15th August

Commissioner Pett and I being invited went by Sir John Winter’s coach, sent for us, to the Mitre, in Fenchurch Street, to a venison-pasty; where I found him a very worthy man; and good discourse, most of which was concerning the Forest of Dean, and the timber there, and ironworks with their great antiquity, and the vast heaps of cinders which they find, and are now of great value, being necessary for the making of iron at this day, and without which they cannot work; with the age of many trees there left, at a great fall in Edward the Third’s time,

by the name of forbid trees, which at this day are called vorbid trees.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1663 – 21st January

Dined at Mr. Ackworth’s, where a pretty dinner, and she a pretty and modest woman; but, above all things, we saw her Rock, which is one of the finest things done by a woman that I ever saw. I must have my wife to see it.

On board the Elias, and found the timber brought from the Forest of Dean to be exceedingly good.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1665 – 20th March

. . . and I full of joy, thence to dinner, they setting me down at Sir J. Winter’s, by promise, and dined with him, and a worthy fine man he seems to be, and of good discourse; and a fine thing it is to see myself come to the condition of being received by persons of this rank, he being, and having long been, Secretary to the Queen-mother.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1667 – 15th March

Letters this day come to Court do tell us that we are not likely to agree, the Dutch demanding high terms, and the King of France the like, in a most braving manner. This morning I was called up by Sir John Winter, poor man! ome in a sedan from the other end of town, about helping the King in the business of bringing down his timber to the seaside, in the Forest of Dean.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1667 – 30th April

Sir John Winter to discourse with me about the Forest of Dean, and then about my Lord Treasurer, and asking me whether, as he had heard, I had not been cut for the stone, I took him to my closet, and there showed it to him, of which he took the dimensions, and I believe will show my Lord Treasurer it.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1671 – July

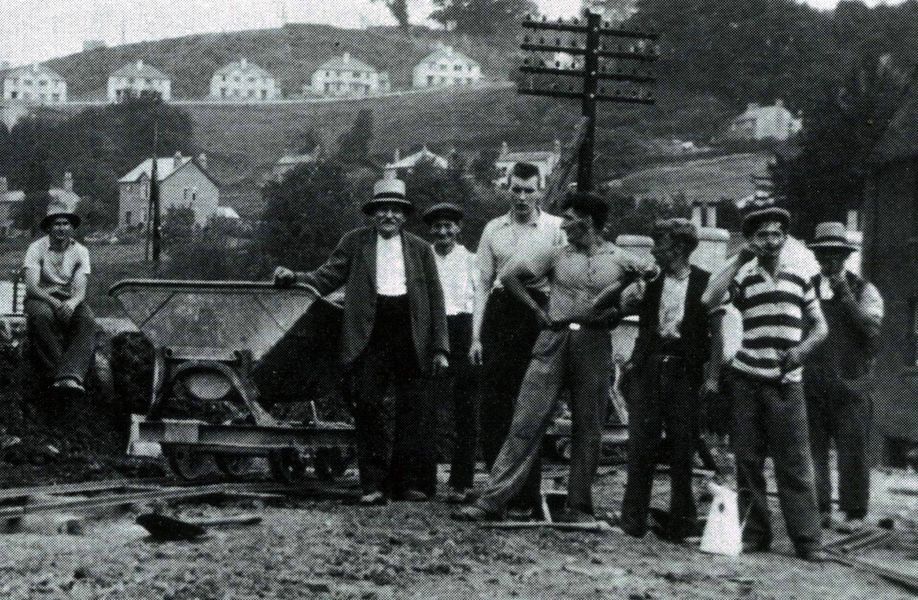

(Pepys, with Lord Brouncker, Commissioner Tippetts, Anthony Deane and four clerks set out from Plymouth on a tour of inspection of the Royal Forests – EH.)

Thence, with their horses and clerks and three bottles of cider, they were ferried across the Severn to Wales, where they stopped at Chepstow and Newnham and visited the iron works. The bill for one of their meals has been preserved – a leg and neck of mutton with carrots 5s., a couple of rabbits 2s. 8d., fruit and cheese 10d., a bottle of claret 1s., a pint of white wine 1s., and bread and beer 4s. 2d., At another meal they ate a leg of mutton and cauliflower, a breast of veal, six chickens, artichokes, peas, oranges and fruit and cheese with a modest 3s. 6d. worth of wine to wash down £1 9s. 7d. of food.

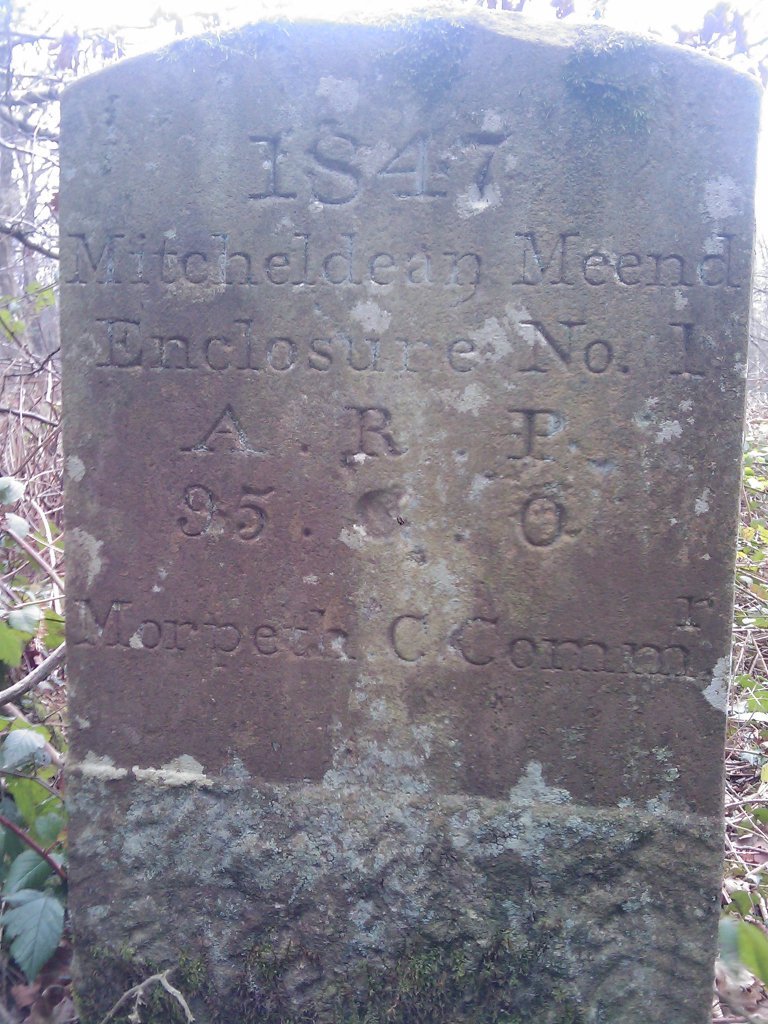

So they came to the Forest of Dean, where they stayed at Mitcheldean and took a survey of the forest. Their Report, which Pepys afterwards presented to His Majesty, was not encouraging. Of the 10,000 trees, about half were oaks, most of them wind-ridden or cup-shaken and not more than 800 of them fit for the service of the Navy. The beeches were in better condition: taking twenty-four average trees scattered over the whole forest and to fell which they gave the Woodward £2 5s. for an encouragement, they found them all sound and good for making four-inch by three-inch planks, though of no use for any other purpose. A great many trees, too, were lying on the ground, having been felled for the building of a new warship at Bristol, but of these few were worth the transporting and all were likely to be useless if they lay much longer.

With a guide and a shilling’s worth of beer, they went on to Gloucester, where they stayed a night and collected their letters from the post-house . . .

This text was taken from ‘Samuel Pepys: The Years of Peril’

Written by Arthur Bryant in 1935

(publisher: The Reprint Society – 1952)