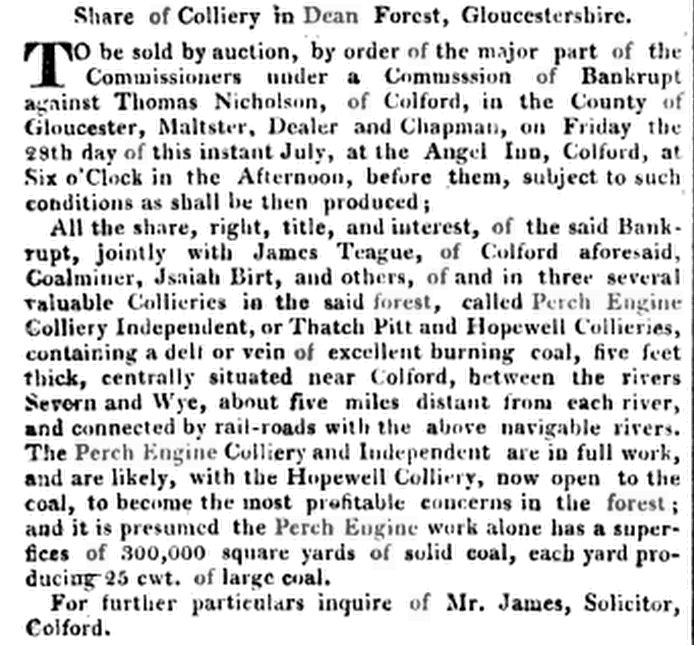

This article in the London Gazette (dated: Saturday, 8th July 1815) mentions: The Angel Inn, Coleford; Thomas Nicholson, James Teague, Josiah Birt, The Perch Engine Colliery, Independent Colliery, Thatch Pit Colliery and Hopewell Colliery.

“The little girl who is the heroine I met within the area of Goodrich Castle in the year 1793 . . .“

Wordsworth and Coleridge: The Lyrical Ballads 1798-1805 (Published by Methuen Co. Ltd., 1903)

We are Seven

A simple child, dear brother Jim,

That lightly draws its breath,

And feels its life in every limb,

What should it know of death ?

I met a little cottage Girl,

She was eight years old, she said ;

Her hair was thick with many a curl

That clustered round her head.

She had a rustic, woodland air,

And she was wildly clad ;

Her eyes were fair, and very fair ;

– Her beauty made me glad.

“ Sisters and brothers, little Maid,

How many may you be ? ”

“ How many ? Seven in all,” she said,

And wondering looked at me.

“ And where are they ? I pray you tell.”

She answered, “ Seven are we ;

And two of us at Conway dwell,

And two are gone to sea.

Two of us in the church-yard lie,

My sister and my brother ;

And in the church-yard cottage I

Dwell near them with my mother.”

“ You say that two at Conway dwell,

And two are gone to sea,

Yet ye are seven ; I pray you tell,

Sweet Maid, how this may be ? ”

Then did the little Maid reply,

“ Seven boys and girls are we ;

Two of us in the church-yard lie,

Beneath the church-yard tree.”

“ You run about, my little Maid,

Your limbs they are alive ;

If two are in the church-yard laid,

Then ye are only five.”

“ Their graves are green, they may be seen,”

The little Maid replied,“

Twelve steps or more from my mother’s door,

And they are side by side.

My stockings there I often knit,

My kerchief there I hem ;

And there upon the ground I sit –

I sit and sing to them.

And often after sun-set, Sir,

When it is light and fair,

I take my little porringer,

And eat my supper there.

The first that died was little Jane ;

In bed she moaning lay,

Till God released her of her pain ;

And then she went away.

So in the church-yard she was laid ;

And all the summer dry,

Together round her grave we played,

My brother John and I.

And when the ground was white with snow,

And I could run and slide,

My brother John was forced to go,

And he lies by her side.”

“ How many are you, then,” said I,

“ If they two are in Heaven ? ”

The little Maiden did reply,

“ O Master ! we are seven.”

“ But they are dead ; those two are dead !

Their spirits are in Heaven ! ”

’Twas throwing words away ; for still

The little Maid would have her will,

And said, “ Nay, we are seven ! ”

by William Wordsworth (1798)

(I get a buzz out mentions of the Forest of Dean and literature. This is an extract from Tennyson’s Pelleas and Ettare.)

King Arthur made new knights to fill the gap

Left by the Holy Quest; and as he sat

In hall at old Caerleon, the high doors

Were softly sundered, and through these a youth,

Pelleas, and the sweet smell of the fields

Past, and the sunshine came along with him.

`Make me thy knight, because I know, Sir King,

All that belongs to knighthood, and I love.’

Such was his cry: for having heard the King

Had let proclaim a tournament–the prize

A golden circlet and a knightly sword,

Full fain had Pelleas for his lady won

The golden circlet, for himself the sword:

And there were those who knew him near the King,

And promised for him: and Arthur made him knight.

And this new knight, Sir Pelleas of the isles–

But lately come to his inheritance,

And lord of many a barren isle was he–

Riding at noon, a day or twain before,

Across the forest called of Dean, to find

Caerleon and the King, had felt the sun

Beat like a strong knight on his helm, and reeled

Almost to falling from his horse; but saw

Near him a mound of even-sloping side,

Whereon a hundred stately beeches grew,

And here and there great hollies under them;

But for a mile all round was open space,

And fern and heath: and slowly Pelleas drew

To that dim day, then binding his good horse

To a tree, cast himself down; and as he lay

At random looking over the brown earth

Through that green-glooming twilight of the grove,

It seemed to Pelleas that the fern without

Burnt as a living fire of emeralds,

So that his eyes were dazzled looking at it.

Then o’er it crost the dimness of a cloud

Floating, and once the shadow of a bird

Flying, and then a fawn; and his eyes closed.

And since he loved all maidens, but no maid

In special, half-awake he whispered, `Where?

O where? I love thee, though I know thee not.

For fair thou art and pure as Guinevere,

And I will make thee with my spear and sword

As famous–O my Queen, my Guinevere,

For I will be thine Arthur when we meet.’

. . .

You can imagine my excitement when I read the following lines in Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation of the Mabinogion (1848):

“I am one of thy foresters, Lord, in the Forest of Dean, and my name is Madawc, the son of Twrgadarn.”

If have now tracked down the original medieval Welsh for this translation in the Llyfr Coch Hergest (The Red Book of Hergest) one of the source-books for the Mabinogion.

“afforestwr itti arglwyd wyfi ynforest ydena. amadawc yw vy enw i uab twrgadarn.”

Here is some more of the text covering the entry and the description of the forester, Madawc:

“ . . .

And on Whit-Tuesday, as the King sat at the banquet, lo! there entered a tall, fair-headed youth, clad in a coat and a surcoat of diapered satin, and a golden-hilted sword about his neck, and low shoes of leather upon his feet. And he came, and stood before Arthur.

‘Hail to thee, Lord!’ said he.

‘Heaven prosper thee,’ he answered, ‘and be thou welcome. Dost thou bring any new tidings?’

‘I do, Lord,’ he said.

‘I know thee not,’ said Arthur.

‘It is a marvel to me that thou dost not know me. I am one of thy foresters, Lord, in the Forest of Dean, and my name is Madawc, the son of Twrgadarn.’

. . . ”

This is the introduction to another White Stag in the Forest of Dean story – more later.

***

English extracts taken from:

The Mabinogion by Lady Charlotte Guest

(Beaker Folk: Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age people living about 4,500 years ago in the temperate zones of Europe. – Encyclopædia Britannica)

The New Stone Age people were succeeded by the “Beaker” folk, so called from a highly distinctive type of pot which was used among them. These people have left very impressive memorials in the shape of stone monuments of large size, from single standing stones called “menhirs” to elaborate stone circles. There are no stone circles recorded in Gloucestershire. Although there are several just across its borders, but in the Dean we still can see the Staunton “Long Stone” at the side of the road between Coleford and Staunton, and the “Queen Stone” at Huntsham. Until fairly recently there were two others, “Long John” at Close Turf, St Briavels, which was destroyed in recent years, and another at Shortstanding, which possibly is the origin of the name of the place if, as some think, it comes from “Short Stone Dun”.

Forest Story by R. J. Mansfield (published in 1964 by the author)

Mustard Gas and the Spruce Drive

Wars have always made heavy demands on the Forest, from the time the Silures rallied to the calls of Caradoc, through the Middle Ages and the undermining sappers, right up to the names lately added to our village memorials. In material things, however, the demand has changed with the years. While there were wooden walls to be built, here was the first source of supply; if it was horseshoes, or nails, or small cannon, the iron mines of Dean produced a share. Then when ships grew from steel plates and the iron industry moved away, timber was needed for pit props, building and a hundred more purposes, so that the woodlands woodlands were stripped far beyond the routine fellings.

The last war brought another need – concealment from enemy aircraft – and in this the forest played a big part. For miles the tree-shaded roads were stacked with explosives and other war materials wherever the verges were wide enough, and many new roads were made in the enclosures. No one will grudge this use, though it did bring with it severe restrictions on movement in the area. But there is reason to feel a lot less satisfied with the removal of (or failure to remove) some of these stores. Even now, five years after (this book was published in 1952 – EH), a big area round the Spruce Drive is dangerous owing to the presence of mustard gas. Admittedly the containers have perished, so that the removal process is slow and difficult, but we are entitled to wonder if much of the trouble is not due to the delay in tackling the job. This is not just a matter of amenity for picnic parties. I have been told by men working on the site that a number of local people have been seriously injured by picking up wood that has been contaminated. There are warning notices, to be sure, but they are unlikely to deter a child from wandering that way, for there are no fences.

The above text is from:

“The Forest of Dean”

by F. W. Baty

publisher: Robert Hale 1952

Mustard Gas in the Russell Enclosure

(I found this on the internet (wikipedia) – EH)

The collapse of Llanberis also lead to the decision to remove chemical weapons from subterranean storage, mainly a large number of bombs containing the unstable and corrosive mustard gas. Harpur Hill had been designated the central store for such devices in April 1940, receiving its first load in June of that year of mustard gas bombs evacuated from France.

In June 1942 it was decided to move the bombs to a remote site at Bowes Moor in County Durham. As an aside, the War Office chemical weapons store was at Russell’s Enclosure in the Forest of Dean, post-war disclosures of the mismanagement there are a little disquietening.

The move of RAF bombs to Bowes Moor began in December 1941 with the bombs initially stored in the open under tarps or in wooden sheds. It was found that the sheep on the moorland would consume the tarpaulins and disturb the bombs, resulting in the addition of sheep-proof fences and gates for the entire site. Fifty new buildings were later added to store the larger bombs. To ease distribution of mustard gas, five Forward Filling Stations were built at or near existing bomb storage sites.

Ammunition Supply Dump (ASDs)

The Salisbury Plain area also contained two of the three British ammunition supply dumps (ASDs) first used for ammunition shipments from the United States – Savernake Forest and Marston Magna. The Third, Cinderford, was in the Forest of Dean near the Bristol ports. The British ASDs areas containing adequate road nets and enough villages to provide railheads. Since the English countryside was too thickly settled to permit depots in the American or Australian sense, the British had stacked ammunition along the sides of roads. If the roads ran through an ancient forest or park with tall trees to hide the stacks from enemy bombers, so much the better; in any case roadside storage made the ammunition easily accessible, an important consideration at a time when fear of German invasion was always present. Each stack of artillery and small arms ammunition was covered by a portable corrugated iron shelter, or hutment, that was usually camouflaged by leaves poured over a wet asphalt coating. Bombs were stored in the open at Royal Air Force (RAF) depots. The first U.S. ammunition depots were activated on 2 August 1942 at Savernake Forest (O-675), capacity 40,000 tons, and Marston Magna (O-680), 5,000 tons. At both, troops were to be billeted in whatever buildings were available – the Marquess of Aylesbury’s stables, farmhouses, a cider mill, and Nissen huts. But for some time to come, all U.S. ammunition depots had to be operated mainly by British RAOC troops. When large shipments of ammunition began to arrive in late August, more depots were needed. A site surveyed by the British but not yet used was found in the Cotswolds, northeast of Cheltenham. Activated as Kingham (O-670) on 11 September, this depot became by early 1943 the largest U.S. ammunition depot in England. On the same day that Kingham was activated, a fourth depot, O-660, was activated at the British ASD Cinderford and soon became the second largest U.S. ammunition depot. The sites for these four depots were selected with ground force ammunition in mind. For air ammunition, three main depots of about 20,000 tons capacity each were required in the first BOLERO plan. Two were established in the Midlands, near Leicester and air bases – Melton Mowbray (O-690) and Wortley (O-695), both activated 30 September. The third was Grovely Wood (O-685) in southern England, activated 2 September. In the meantime, SOS began to store bombs and other air ammunition at Savernake, Cinderford, Kingham, and Marston Magna, which then became composite, rather than ground force, depots.

This text is an extract from:

“The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront”

by Lida Mayo

See also:

Acorn Patch – Explosive Ordnance Depot

Photos Taken in the Forest of Dean

Berry Hill, being one of the larger villages in the central, high and most populous ridge of the Forest, has two chapels, one a Methodist outpost, Zion, and the other a ‘free church’, Salem. Zion and Salem, Salem and Zion, twin guardians of the village, not above a great deal of jealousy for each other; and at times in the past, their associations were as much social and political as narrowly biblical, for this form of Christian fundamentalism has often been closely related to the history of the English and Welsh working classes, and our Labour movement. Salem and Zion were once, undoubtedly, the two most important places in the village, revered far more than the band and the rugby team. Their prim stone hulks were the solidification of almost everything judged important in the life of the district gathered immediately around them. Half a mile away there would be another chapel, and, half a mile onwards again, yet another. Each a ruling centre, with a ruling cabinet and a discipline as immutable as an established natural law.

The preceding text is taken from The Changing Forest

by Dennis Potter

(publisher: Secker and Warburg, 1962)

Samuel Pepys was a fascinating character. He wrote his famous diary between 1660 and 1669. He lived through the Commonwealth and saw the return of Charles II, the Plague and the Great Fire of London.

As the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, his responsibility was the Navy, and thus the Forest of Dean, which supplied the timber to build the ships.

He was born in 1633 and died in 1703. His life covered the reigns of Charles I, the Commonwealth, Charles II, James II, William & Mary and Anne.

1662 – 25th February

Great talk of the effects of this late great wind; and I heard one say that he had five great trees standing together blown down; and, beginning to lop them, one of them, as soon as the lops were cut off, did by the weight of the root, rise again and fasten.

We have letters from the Forest of Dean, that about 1000 oaks and as many beeches are blown down in one walk there.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1662 – 20th June 25th

Up by four or five o’clock, and to the office, and there drew up the agreement between the King and Sir John Winter about the Forest of Dean; and having done it, he came himself (I did not know him to be the Queen’s (Queen Henrietta Maria) secretary before, but observed him to be a man of fine parts); and we read it, and both like it well.

That done, I turned to the Forest of Dean, in Speed’s Maps, and there he showed me how it lies;

and the Lea-Bayly, with the great charge of carrying it to Lydney, and many other things worth my knowing;

and I do perceive that I am very short in my business by not knowing many times the geographical part of my business.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1662 – 15th August

Commissioner Pett and I being invited went by Sir John Winter’s coach, sent for us, to the Mitre, in Fenchurch Street, to a venison-pasty; where I found him a very worthy man; and good discourse, most of which was concerning the Forest of Dean, and the timber there, and ironworks with their great antiquity, and the vast heaps of cinders which they find, and are now of great value, being necessary for the making of iron at this day, and without which they cannot work; with the age of many trees there left, at a great fall in Edward the Third’s time,

by the name of forbid trees, which at this day are called vorbid trees.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1663 – 21st January

Dined at Mr. Ackworth’s, where a pretty dinner, and she a pretty and modest woman; but, above all things, we saw her Rock, which is one of the finest things done by a woman that I ever saw. I must have my wife to see it.

On board the Elias, and found the timber brought from the Forest of Dean to be exceedingly good.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1665 – 20th March

. . . and I full of joy, thence to dinner, they setting me down at Sir J. Winter’s, by promise, and dined with him, and a worthy fine man he seems to be, and of good discourse; and a fine thing it is to see myself come to the condition of being received by persons of this rank, he being, and having long been, Secretary to the Queen-mother.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1667 – 15th March

Letters this day come to Court do tell us that we are not likely to agree, the Dutch demanding high terms, and the King of France the like, in a most braving manner. This morning I was called up by Sir John Winter, poor man! ome in a sedan from the other end of town, about helping the King in the business of bringing down his timber to the seaside, in the Forest of Dean.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1667 – 30th April

Sir John Winter to discourse with me about the Forest of Dean, and then about my Lord Treasurer, and asking me whether, as he had heard, I had not been cut for the stone, I took him to my closet, and there showed it to him, of which he took the dimensions, and I believe will show my Lord Treasurer it.

The preceding text is taken from The Diary of Samuel Pepys

(publisher: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1905)

1671 – July

(Pepys, with Lord Brouncker, Commissioner Tippetts, Anthony Deane and four clerks set out from Plymouth on a tour of inspection of the Royal Forests – EH.)

Thence, with their horses and clerks and three bottles of cider, they were ferried across the Severn to Wales, where they stopped at Chepstow and Newnham and visited the iron works. The bill for one of their meals has been preserved – a leg and neck of mutton with carrots 5s., a couple of rabbits 2s. 8d., fruit and cheese 10d., a bottle of claret 1s., a pint of white wine 1s., and bread and beer 4s. 2d., At another meal they ate a leg of mutton and cauliflower, a breast of veal, six chickens, artichokes, peas, oranges and fruit and cheese with a modest 3s. 6d. worth of wine to wash down £1 9s. 7d. of food.

So they came to the Forest of Dean, where they stayed at Mitcheldean and took a survey of the forest. Their Report, which Pepys afterwards presented to His Majesty, was not encouraging. Of the 10,000 trees, about half were oaks, most of them wind-ridden or cup-shaken and not more than 800 of them fit for the service of the Navy. The beeches were in better condition: taking twenty-four average trees scattered over the whole forest and to fell which they gave the Woodward £2 5s. for an encouragement, they found them all sound and good for making four-inch by three-inch planks, though of no use for any other purpose. A great many trees, too, were lying on the ground, having been felled for the building of a new warship at Bristol, but of these few were worth the transporting and all were likely to be useless if they lay much longer.

With a guide and a shilling’s worth of beer, they went on to Gloucester, where they stayed a night and collected their letters from the post-house . . .

This text was taken from ‘Samuel Pepys: The Years of Peril’

Written by Arthur Bryant in 1935

(publisher: The Reprint Society – 1952)

Offa’s Dyke can be seen in several places in the Forest. It is first recognisable just in the western end of the Lydbrook Viaduct. From here it shows at intervals until the road to Bicknor cuts through its path, and here it is evident, both on the bank and towards the top of the hill opposite, whence a combination of dyke and cliff marked the edge of Mercia as far as Symond’s Yat, where it seems to merge with the vallum of the Rock Promontory Fort.

From this point no trace of it can be seen for ten miles since the cliffs are so high, but just below Redbrook it becomes visible again, and can be followed fairly easily until it comes to an end in a bunch of scrub in a field at Tutshill, near to the old look-out tower which was later erected as an outpost of Chepstow Castle. A continuation of the Dyke runs across the Beachley Peninsula to reach the Severn at Sedbury, and may be traced on portions of the higher ground. Here it bears traces of being used for later defence works, but at certain spots it retains a nearly perfect form.

The text above is from:

“Forest Story”

by R.J. Mansfield

publisher: the author 1964

Most inexplicable of all the mark stones are those with clean-cut grooves running from top to bottom of an upright or ‘long’ stone.

The Queen Stone in the horseshoe bend of the Wye near Symond’s Yat is a fine Herefordshire example. It measures about 7 feet 6 inches in height, 6 feet broad and 3 feet wide. The south-east face has five grooves, the north-west face three grooves, the north-east end two grooves, and the south-west end one only.

The grooves die out before reaching the ground, but appear to continue in an irregular way over the apex. They are all much alike in width – from 2 inches to 2½ inches, but vary in depth from 3 inches to 7 inches, being much deeper than they are wide. It seems quite impossible that they should result from any natural cause.

The top of the stone is irregularly corroded, and the probability of this being caused by fire presents itself. I tried the insertion of broomsticks in these grooves, but the tops projecting on opposite sides were too irregular for such a method to have been used for sighting.

There seems to be no legend attached to this stone, and it aligns with other points. Whether it is a sacrificial stone remains a surmise.

The above text is from:

“The Old Straight Track”

by Alfred Watkins

publisher: Methuen 1925

An Edition of the 1798 London Edition

david rosenberg

Tales from my family tree

bloggings about beards, beer & socialism

perambulations around london ( .. and beyond)

BA Hons & MA in Fine Art + Post Grad Printmaking

Historical bits and pieces about crime and punishment in Gloucestershire

A Private History of a Public City

Pop in any time for a cup of tea and a natter!

Writer and teacher

looking after our libraries

Sustainable Agriculture in the Forest of Dean

Just another WordPress.com site

The Renaissance is not a time, but a temperament (Ezra Pound)

on a mission to keep our Forest in public hands and free from fracking

A Blog for Italian Language students from Italian Language teachers and students